Finger by Finger?

By Emma Hutchison (1980-2024)

8 June 2024

Published posthumously on 8 April 2025

With minor edits by Emma’s husband, Roland Bleiker

This is the 11th and last entry of Emma’s blog Dialysis Days, which started in 2015 and documents Emma’s life on dialysis and with kidney transplants.

More context about Emma is at the end of this blog and in this Tribute and this Photoblog.

Prologue

It has been more than three years since I posted a blog.

And it has been more than four years since I restarted dialysis; since my second kidney transplant failed. I never was a frequent blogger, but I posted every now and then and part of the reason I did was social. To upkeep or find some kind of social connection – however superficial or distant.

The years since I restarted dialysis have been unfathomably difficult. Health-wise, it feels like there has only been bad luck. There have been constant horrible complications. Mini catastrophes arrived tsunami-like, crashing in on us, in six-month waves.

Many wonderful things also happened in our life. Through the waves of pain we wanted – needed – to just get on with living. And we have tried to do my health ‘right’: to take care of us as best we can.

But my health – my illness – has kept butting into our life, time and time again.

In her work understanding the sociality of illness, philosopher Havi Carel discusses how there is something frighteningly personal about illness – and that it is these personal aspects that make illness so daunting. “You can separate yourself from painful things… people, places. You can throw away a pen that doesn’t work, but you cannot throw away your head with a headache in it.”

Carel also points to an overwhelming tension: illness may be unique and singular and experienced in ways no-one else can understand. Yet, she argues that we all need to try harder to focus our minds on the negation of health, on what the absence of health may be like. “Illness travels over everything in our life. It is really important for our attempts to understand human existence; to appreciate shared experience we need to appreciate what happens when your body begins to fail.”

“[T]he vast majority of us will die of an illness… It is universal, it is fundamental to our being,” Carel reminds us.

My body has for long – for the 25-30 years I have lived with kidney failure - been traversing a tightrope of living and failing; of life and death.

The entry below I wrote some time ago. The original draft is dated 20 September 2023.

Finger by Finger?

We are sitting in a hospital clinic consultation room. The hand surgery clinic at a research-intensive public hospital. We have been here, lined up, since 7:30am. My private hand surgeon is here somewhere too. She’s asked for a review from the whole surgical team. A collective decision. A jury. Or so it feels.

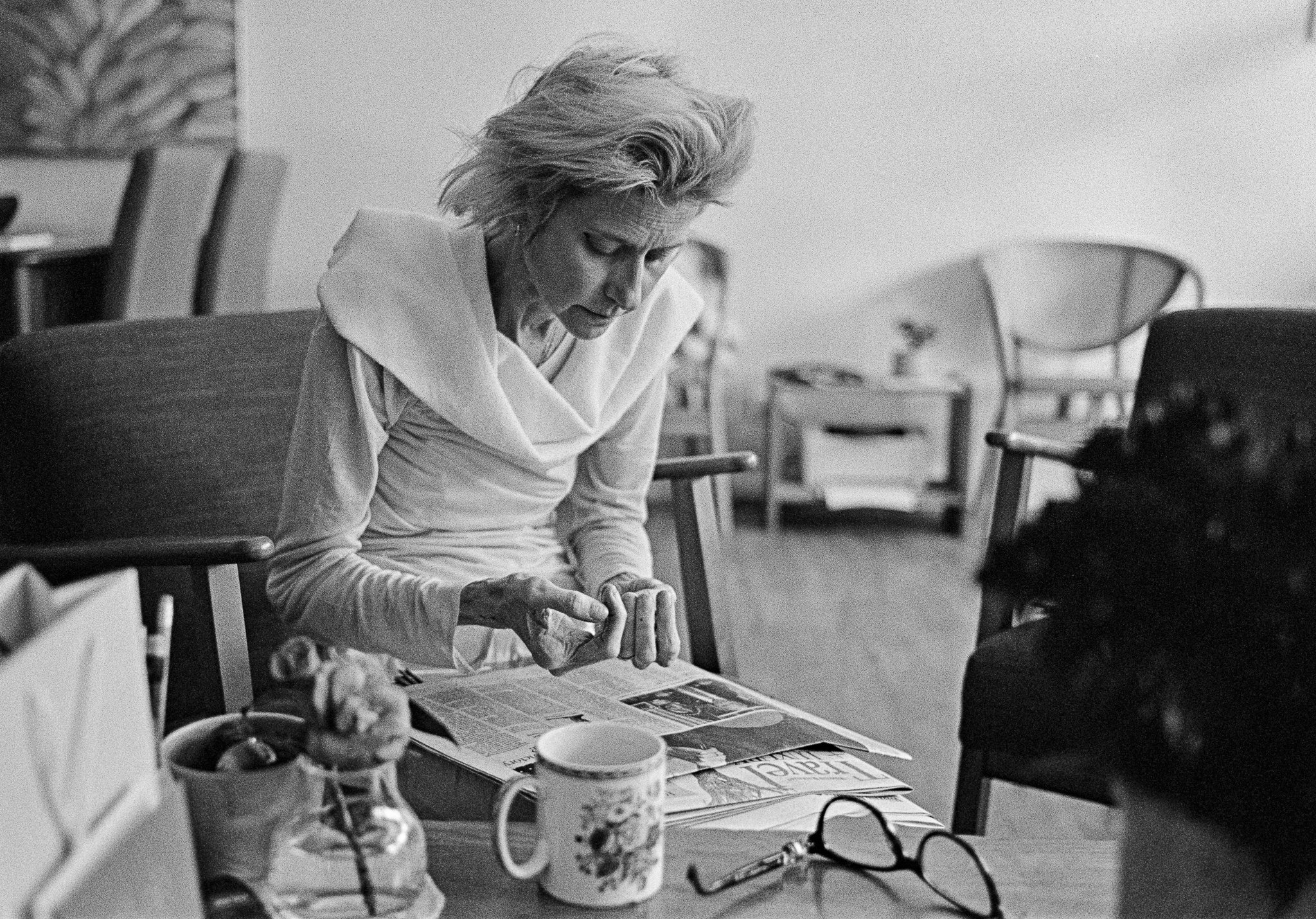

We are here about my index finger. My right index finger. I’m right-handed; so, it’s my dominant hand. It’s the hand – the finger even – that I use most: to type, to text, to fidget, to think through, when I write. To be me, it seems.

An older surgeon, perhaps the most senior or the ‘in charge’, enters the room. He stands over me, studying my finger.

“Show me how much you can bend it.”

I try bending it inwards towards my palm, as hard as I can. But it is lumpy, and grossly swollen, more than twice its normal size. It is throbbing with inflammation.

“Hmph. Are you using it?”

“No.” I speak clearly.

“Why not? Is it pain or lack of mobility?”

“It’s both.”

“Sounds like you are better off without it. Sounds like we ‘get rid’ of it.”

We are silent.

I am – we are - not fazed, exactly. I am used to doing what doctors - my medical team - tell me is best.

But we do sit silent for a moment. I am searching my mind, thinking through the logic, thinking through everything we know or think we know and trying to pinpoint the things we don’t. I think through the consequences of both paths. Removing the finger. Keeping the finger. I try to think though what questions we have while we have so many specialists and surgeons buzzing about us.

My partner, my love. He is right beside me. He always is.

We are talking about ‘losing’ my finger. We have been talking about it seriously for a couple of weeks. It has gotten to the point where removing – amputating – my finger does not seem outside the realm of what’s possible. But maybe it is only now sinking in.

How did we get here?

Where even is ‘here’? I only have my own relativity for comparison. I have come to call this “the Emma health spectrum.” But even on this, I have no idea where we are. I am thinking my spectrum might need recalibrating, shifting, again.

It is ‘here’ though that I make my own decision. I have to get this done. I have to get all of this ‘out’ – what feels like a big dark mass of everything my body and mind have endured together with my fears and anticipations of what is to come. Not for you, my reader. Well, if I’m truthful, perhaps partly for you. What if we all knew of the lived experience of illness and disability?

But no, I have to get it out for me.

I once wrote that chronic illness may be – paradoxically – something that we need to let go of in order to be free.

But the place we are at has no metaphors.

It’s the silence that I need to get rid of. It’s the silence of which I must speak.

In her novel that retells the trauma of totalitarianism, The Land of Green Plums, Herta Müller writes, “the words in our mouths do as much damage as our feet on the grass. But then so do our silences.”

My writing in this blog has so far searched to tell of the trauma of living with end-stage kidney failure, but it has been in such a palatable, sanitised way. To me, it’s as if I have packaged the lived experience of kidney failure – different periods in my life: commencing dialysis, two kidney transplants, three different dialysis fistulas, dozens of surgeries, thyroid cancer, further dozens of ‘minor’ procedures, tests, scans – tidily into a box with a perfect neat ribbon. I’ve beautified it. Aestheticized it. Fetishized it. Sure, readers have been aghast in the past. Shocked. Surprised. Horrified. Grateful that I have written what I have. But these days I look back and can only see how my writing is a half-truth.

***

My writing has mirrored my own search to fill life with light and joy and opportunity and love.

But now the light I want to shine is on to the dark.

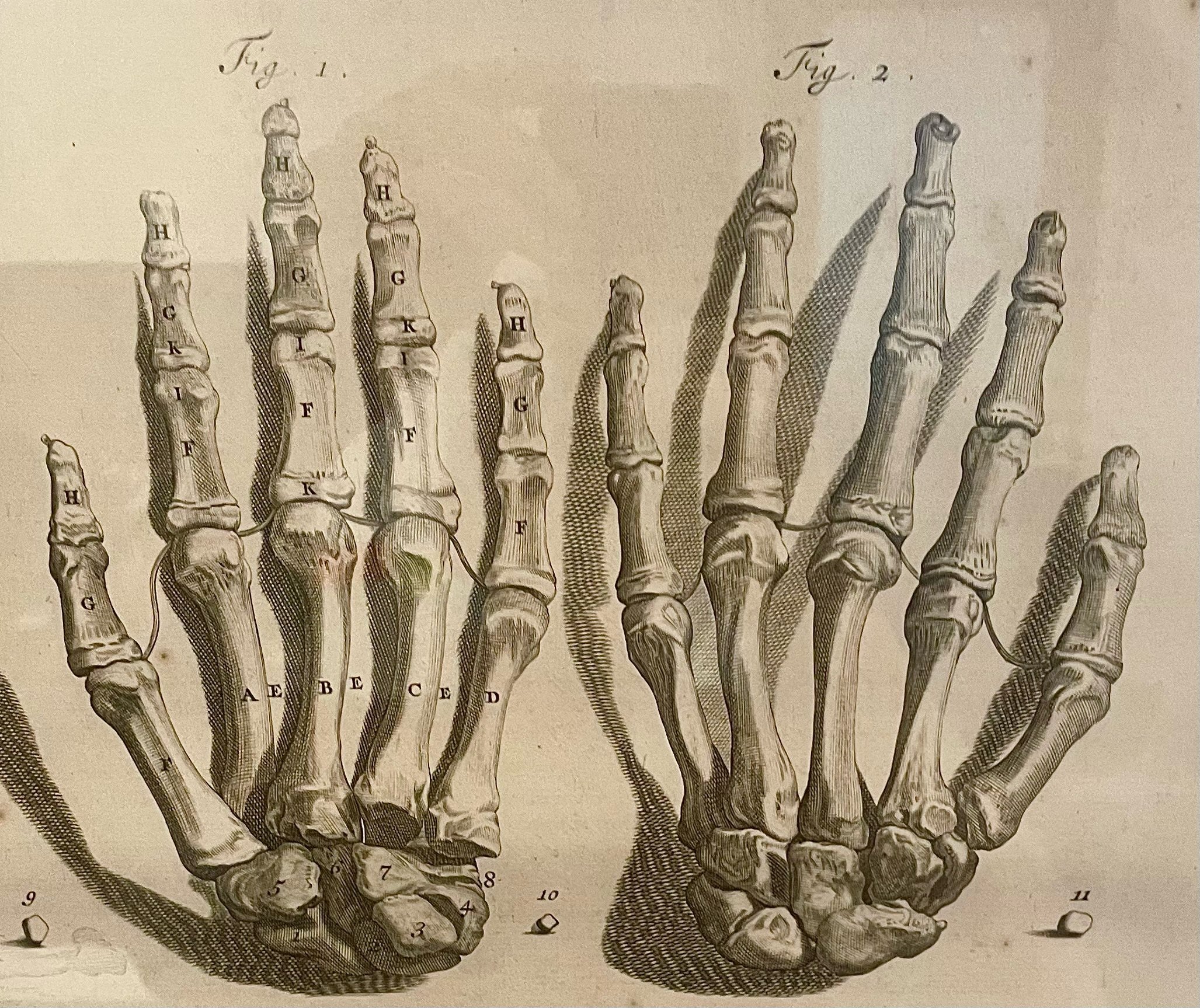

Over the past two to three months, surprisingly fast, my finger has been flooded with a calcium compound that is the chemical result of a body having excessively high phosphate levels.

This is one thing kidneys do: kidneys process and eliminate phosphate, which is in almost everything we eat but especially in foods high in protein, such as dairy, meats, or foods high in preservatives. Kidneys are amazing like this. We cannot design a chemistry lab that would do better – or one that can even do the same.

Our bodies are pretty amazing too, because when kidneys fail, they do what they can to find a balance. In this instance, the body leaches calcium from wherever – bones, typically – to compensate for the phosphate. It is the resulting calcium substance that is my problem. It is like a thick gluggy sticky white toothpaste, which eventually becomes so concentrated that it sets rock-hard. For me, it is everywhere, slowly filling my body. It’s in my toes and feet. My elbows. Fingers. Arteries. Veins. Lungs.

This is one of the realities of long-term end-stage renal failure. Of living with insufficient kidney function for a long time. More than 25 years. It would all have started when I was around 14.

I hear my specialist’s voice – her soft clear lull – pulling me back to the room.

“So you see, Emma, your finger, this finger. It is simply getting to the end of its life.”

She has been in and out, leaving us to talk quietly together many times. It is now just the three of us. She speaks softly. She is looking at me eyes wide in understanding but also focused by clarity. She hopes I see too.

I have always thought I would beat it. Kidney failure. That I would win. And, sure, we can redefine what is meant by winning - I did this long ago.

But one day my body will be beaten.

Maybe it will be sooner.

Hopefully it will be later.

But sadly it will be beaten.

How will it be?

Will it be finger by finger?

One finger, at a time?

Epilogue

By Roland Bleiker

Emma’s blog starts and ends with question marks: “Will it be finger by finger?” “One finger, at a time?”

The question marks became obsolete soon after Emma finished the latest draft of this blog, in June 2024.

We transitioned into palliative care.

The pain relief from the amputated index finger gave us bit of breathing space. But not for long. Emma’s middle finger on the same right hand eventually became so full of calcium, so inflamed, so excruciatingly painful that it too had to go if we wanted to extend out lives together by a few weeks or perhaps even months. And so Emma had a second finger amputated on her right hand.

Finger by finger.

And then came her toes. And her feet and her elbows. And then her lungs got worse and worse. And then more, and more.

Emma called it “death by calcium.”

***

“Finger by Finger?” was difficult to write and close to Emma’s heart. It was perhaps her most honest blog entry, the one in which she did not hold back about what it means to live with chronic illness and facing death.

Amputating a finger was a minor procedure compared to dozens of other surgeries Emma had. But it had major consequences.

Losing the index finger of her right hand made it difficult for Emma to carry out basic daily tasks because her entire left arm had been paralysed over a year before, following a massive hematoma that required emergency surgery.

Losing her right index finger was also symbolic: it cut right through to the core of Emma’s identity and passion: her writing, her being.

It made us all too aware that the end is not far away.

This is why Emma hesitated to publish this blog entry and, in the end, never did. She loved life and she lived it to the fullest. She did not want to become known as the dying person. She did not want pity. She wanted to live as normal and as fulfilling a life as possible for every single minute she had left. And this we did, even though our days became impossibly difficult.

***

Emma worked on several versions of this blog for almost a year. The first draft was written in September 2023 and was far longer. There were substantially revised versions dated 29 October 2023; 22 November 2023; 20 April 2024 and then, the present stripped-down version, is dated 8 June 2024.

The blog published here is almost the same version as Emma’s final draft. When editing I compared the different drafts. I ended up making only minor editorial changes, particularly in passages she flagged for me. For instance, she was not sure if the Herta Müller quote should be in the text or appear as an epigraph. I opted for the text because I found that Emma’s quest to hang on to life, finger by finger, became more important than the struggle to break through the silence of illness.

The photographs featured above were chosen by Emma specifically for this blog. The ones below I picked to provide readers with a bit more context.

I will publish a more detailed photo-essay that documents Emma’s pain and suffering. This I promised to Emma. It will be both a supplement and a contrast to my Portraits of Courage and Curiosity. But I am not ready for this task.

Before Surgery

After Surgery

Sources

Havi Carel, Illness: The Cry of the Flesh. London: Routledge, third edition, 2008/2019.

Havi Carel, Phenomenology of Illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.